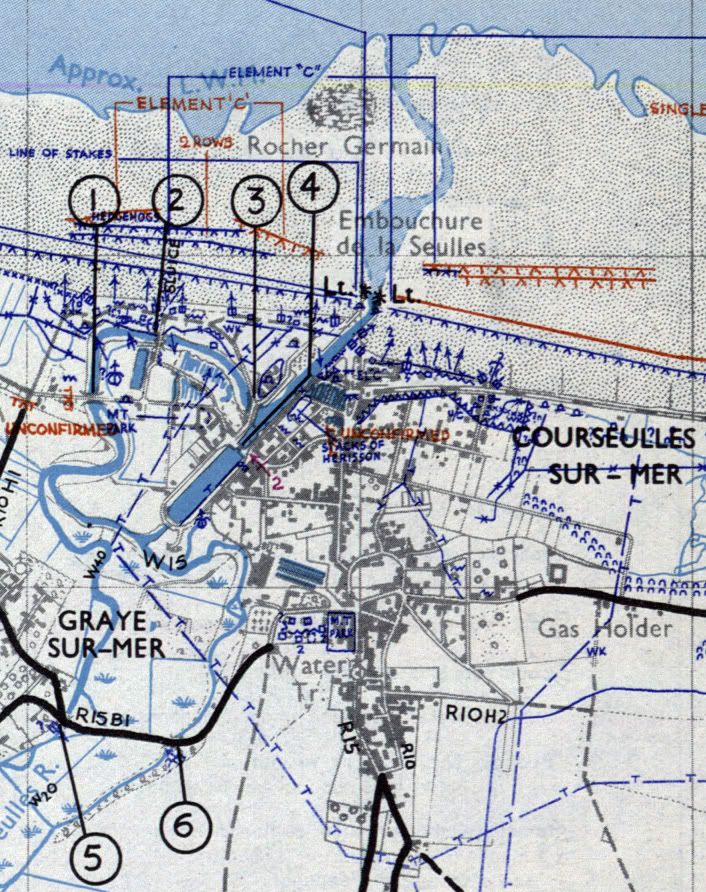

For the cuts, I decided to use straight vertical cuts to form the main shapes. This meant cutting the sheets apart, as the main flow of the rivers is from corner to opposite corner on the boards. This is the main reason for changing the orientation for the river boards: having them run north-south in their long direction meant that in other modular arrangements of the boards I can create a longer river about 8' long, while using one river board will always cut a single corner of the table. Otherwise, the convoluted water courses would have made the boards unplayable in other arrangements. The other adjustment to my thinking was that I did not want the join between the river boards at the beach end to come right to the edge of the beach - at this stage I also started planning the dunes that would need to project onto the beach tile, incidentally giving more space for fortifications and maneuver.

Once the main cuts were made, I then began cutting the slopes/bevels for the riverbanks, trying to maintain long continuous cuts around the curves. In most areas I cut these riverbanks with a broad, shallow slope to accentuate the various elevations, but in some of the tighter turns I cut the banks steeper. In play terms, this would allow figures to take some cover on the riverbanks. Around the fishing harbour, I left the straight cuts in place. You can see in one of these images that I adjusted the plan again to help with playability and avoid creating too many dead zones where miniatures could not maneuver.

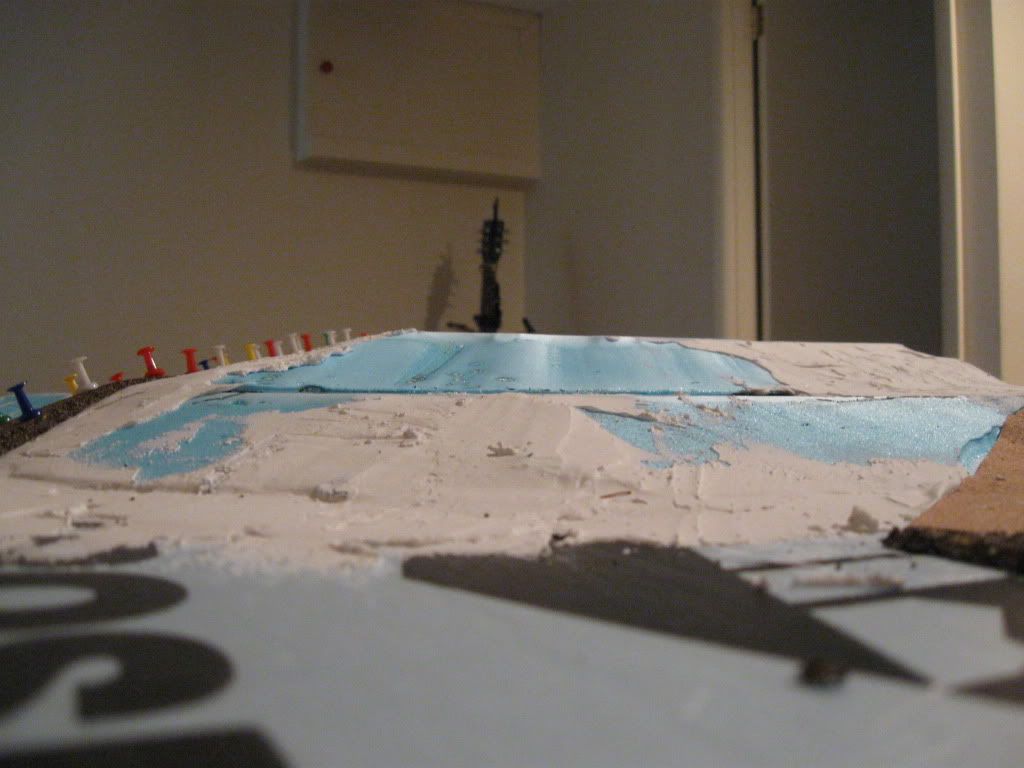

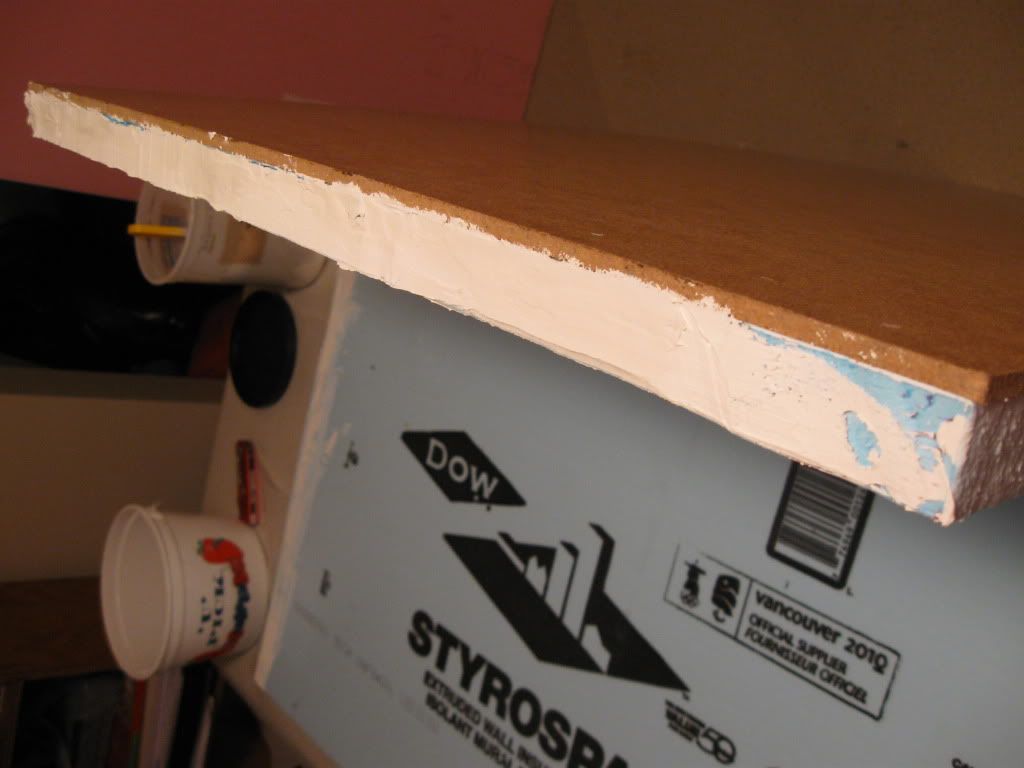

Once the foam pieces were cut, I went back to the beginning and glued these pieces down to the hardboard, then framed these boards underneath. Then these boards needed plaster to cover some of the irregularities and melted spots from the cutting, followed by texture.

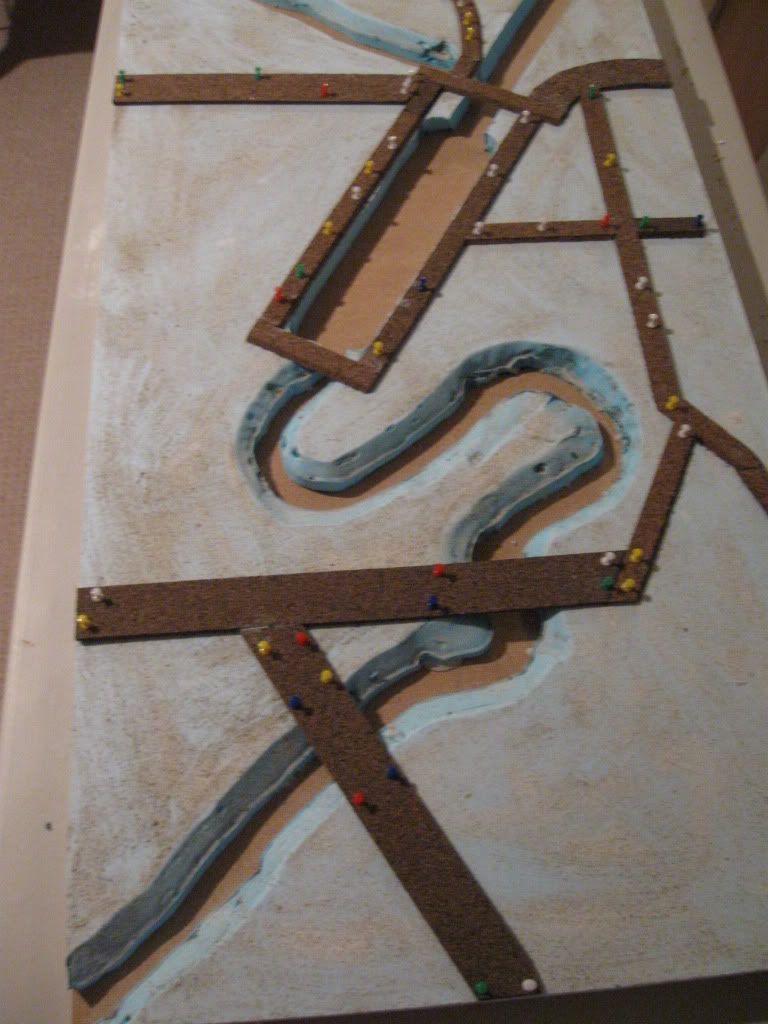

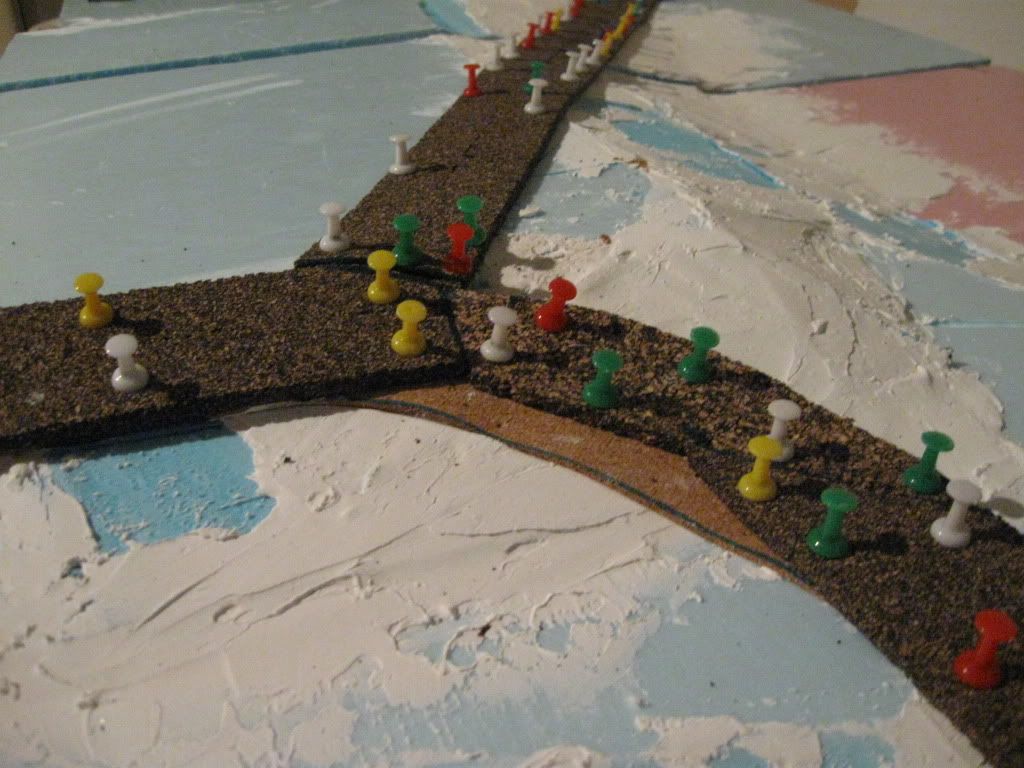

Next came the roads - again a more complex process because of the elevations and bridging. Most stretches of road needed to be pinned while drying. One area of doubt I have about the boards to date is the bridging: extending the cork road to bridges gives a stable and permanent structure, but obviously the bridges don't look much like actual bridges.

The roads were even more carefully planned because of the riverbanks and the tighter spaces for creating connections. Below are the sketch plan and the final results for the two boards' roads: